The area that through most of historic times has been known as Persia , has had a colorful but turbulent history. It has suffered invasion after invasion. Some of these invasions have led to a flowering of high culture, some just the destruction of the current culture.

The Seljuk Turks invaded the area early in the 11th century (1037 AD) and ruled the area for about 2 hundred years before the Mongol’s attacked in the early 13th (1220 to 1235 approximately). The Seljuk culture was one of the Golden Ages of the Persian Arts. It was a time of beautiful ceramics, textiles and metalwork. Unfortunately for us, the Mongol conquest destroyed most of the artifacts of the Saljuki culture. A few remain, and some of the most intriguing are a group of Stucco figures.

The finding of a photo of one of the stucco figures is what started me on this quest for information about the Seljuki. See Figure 1.

When I first saw this stucco carving (figure 1), I assumed that the label was incorrect. I thought that it was a woman not a man. I had never seen a feathered headdress with the three prominent feathers except in female headdresses. Now, these were later than the stucco carving, but I had only found them on women’s headdresses.

I was wrong, but I did not find out until I had found more of the stucco carvings (see The Art Bulletin below). There I found a treasure trove of 3-dimensional Persian art works. The article “Persian Islamic Stucco Sculptures” has photos of over 24 different stucco pieces. In the article Mr. Riefstahl states

“I will not attempt to discuss these stucco sculptures from the angle of the history

of costume, as this would be a study in itself, necessitating the comparison

of our sculptures with a vast amount of other material in miniatures, paintings,

ivory carvings, stone carvings, ect.”

This is my attempt to start this research; I feel that it is a project that will be continuing for a long time.

Male Costume

As usual in Islamic art, we find more illustrations of males than females. Most of this is cultural, in the Middle/Near East especially in Islamic countries, women are encouraged to not put themselves forward or to be hidden away from others not of their family. In times of invasion this was probably even more so.

Overall the wardrobe of a Seljuk gentleman would consist of underwear pants, a shirt, pants, coat/tunic with sash, coat, boots or shoes and headdress/cap. These items would vary with the age and position of the gentleman. The upper garments, when they show the neckline, show a rounded neckline. And if there is an opening, it is down the center front. Actually the most identifiable

item on the whole costume for time placement is the fact, that unless it is a garment for lower body, it has a ‘Tiraz’ band of some type.

Tiraz bands can represent a gift of fabric from the current ruler, a blessing or just a decorative band at the bicep of the arm. A lot of the surviving examples do have writing on them. The Stucco figures do have Tiraz on the arms but the writing can not be translated according to the article. In studying other art work, I find a multitude of different designs – Knot work, geometrics as well as stylized writing.

The younger or more active man is usually shown in variations of the basic dress. Usually his main garment, wherether it is a loose coat or one of the tunic coats, in length it falls just below the knee or mid-calf. It has long sleeves and opens down the center front. His boots comes to approximately the same point.

|

|

I have not found a piece of art work from Persia that shows the outer pants. I can only surmise that they are present, since they are shown occasionally in art work from Egypt a little later. We do have a couple of pieces that show the underwear pants. They show a loose fitting light colored (most likely white linen) pant anywhere from just below the knee to ankle length.

|

|

You will see a couple of different hats with the shorter coat. A cap with a turned up brim (think of a baseball cap with the brim flipped up) usually edged in black (most likely silk). A Pillbox shaped hat, some times decorated with feathers or a frill in front. And a wide band decorated in front and worn with a short veil. The hair is worn long, sometimes with the front braided with loops at the bottom.

|

|

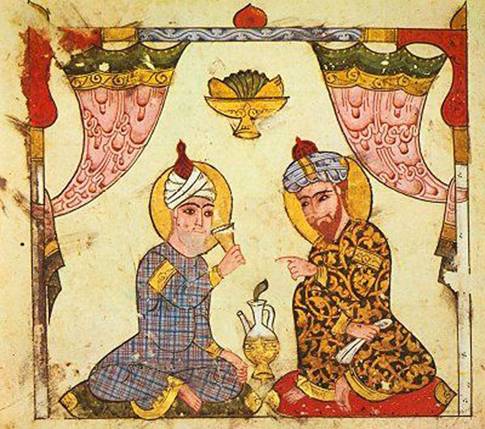

The older or more scholarly are usually shown in a long robe and turban. I feel this more in line with a caftan or long Tunic in cut. No openings show in the art work, this may be artist convention though. I feel that there had to be some kind of opening at the neck at least, since the art work show a high neckline.

This is always shown with a turban and usually with a full beard. Some times a stole of some type draped around the body.

|

|

|

|

Female Costume

From what I can find the woman’s costume in the Seljuki culture was a long loose gown with long trumpet shaped sleeves Triaz bands are apparent on the sleeves which could have had extra length (according to one dish showing a dancer Figure 13). Jewelry is apparent in the art works, necklaces and earrings.

One question that I have been asked is where ever the Sljuki ladies ever wore the decorated loose coat and my answer is that I do not know for sure. But…… I do think that they did wear a garment similar to it given the climate in areas of Persia . The main problem is that none of the art work I have seen shows any thing similar.

Most ladies are shown wearing a hat and most likely a veil. The hats seem to follow the same patterns as the men (cap with turned up brim and pillbox). One of the stuccos figures shows a hairstyle that according to art works continued on for about 200 hundred years.

|

|

|

Fabrics

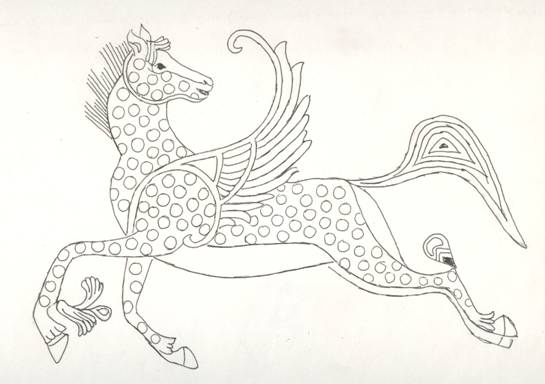

Here are a few actual fabrics from the Seljuki culture. These are all from Masterpieces of Persian Art and are mainly compound cloth of Silk. Most of the patterns are high contrast. Colors almost seem to have been copied from ceramics.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Detail of Fabric pattern taken from a Ceramic plate | |

Patterns

My patterns are line drawing of the basic cut of the garments, they are supposition.

My method of patterning is not fool proof. They are based on rectangular construction methods.

Men

Underwear

|

|

Shirt

Tunic coat

|

|

Loose Coat

|

|

Caftan / Loose Robe

|

|

Women

Gown

|

|

|

|

The key hole neckline is another option but the only neckline I have been able to document is the square. Most of the art work does not show the necklines on ladies very clearly to be sure of other styles.

The Mongol conquest of the 13th century affected more than just the areas that they conquered directly. The push of the invaders caused many to abandon the land of their birth and move westward. But we are indebted to this invasion, because by abandoning their home and moving to Egypt and the other Islamic nations further west, the Seljuk culture change and grew. The Mukluk’s of Egypt and Andalusia of Spain are direct ancestors of Seljuk’s of Persia .

Illustrations

Figure 1 Masterpieces of Persian Art, plate 66, from the collections of Mrs. Cora Timken Burnett

Figure 2 Ciba Symposia, 13 th Century from an Arabian translation ofMateria medica of Dioscorides. Stockholm p1860

Figure 3 A Survey of Persian Art, Twill shirt with Triaz bands, from the Textile Museum in DC.

Figure 4 Polychrome Stucco Figure, Detroit Institute of Art

Figure 5 Figure of a Youth, Art Bulletin from the collection of H. Kevorkian

Figure 6 Islamic Art, detail of miniature showing labors at work, ill. 98

Figure 7 Minor Arts of Islam, Fig 68, Scenes from Firdausi c 1200AD

Figure 8 Statuette of a Retainer, The Art Bulletin, property of Stephen Bourgeois

Figure 9 Statuette of a Youth, The Art Bulletin, Kaiser Friedrich Museum

Figure 10 Two Seated Men, 1237, from Serving the Guest web site

Figure 11 The Minor Arts of Islam, fig. 64 and 65, Two Lusterware bowls

Figure 12 Female figure, The Art Bulletin, Victoria and Albert Museum

Figure 13 Lakabi Dish, Islamic Art, fig. 68

Figure 14 Lady’s Stucco Head, The Art Bulletin, Kaiser Friedrich Msueum

Figure 15 My sketch of the Stucco head above.

Sources

Masterpieces of Persian Art, Arthur Upham Pope, 1945, the Dryden Press

A Survey of Persian Art, edited by A. U. Pope, 1939

The Art Bulletin, Vol. XIII, No. 4, December 1931, “Persian Islamic Stucco

Sculptures” by Rudolf M. Riefstahl

The Minor Arts of Islam, Ernst Kühnel, translated by Katherine Watson,

1971, ISBN 801405637, LLC# 75-110331

Ciba Symposia, Vol. 6 No.5 -6, Aug. – Sept. 1944, “Arabian Pharmacology”,

Ciba Pharmaceutical Products, Inc.

Islamic Art, David Talbot Rice, 1985, ISBN 0500201501

Persian Art, An Illustrated Souvenir of the Exhibition of Persian Art, 1931,

Hudson &Kearns, LTD.

Web-sites

The Detroit Institute of Art http://www.dia.org

The Metropolitan Museum of Art http://www.metmuseum.org

The Cleveland Museum of Art http://www.clevelandart.org

The Textile Museum http://www.textilemuseum.org

The Victoria and Albert Museum http://www.vam.ac.uk

Serving the Guest: A Sufi Cookbook and Gallery http://www.superluminal.com/cookbook/index_gallery.html

Sayyida Dinah bint Ismai’l

Dinah Tackett

July 16, 2004